Display of Virtual Braille Dots by Lateral Skin Deformation: Feasibility Study

table of contents1. Introduction

1.1 Braille Displays

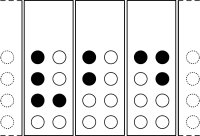

Louis Braille's reading and writing system has given the blind access to the written word since the early 19th century. Braille characters replace the sighted's written letters with tactile equivalents. In the Braille alphabet, each character consists of an array of two columns and three rows of raised, or absent dots. Traditionally embossed on paper, Braille has more recently also been provided by refreshable Braille displays that generally add a fourth row of dots. Refreshable Braille displays were initially the only type of computer interface available for the blind. Despite the growing popularity of more affordable speech synthesis hardware and software, refreshable Braille remains a primary or secondary access medium for many blind computer users.

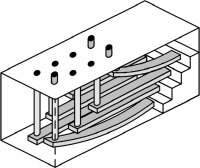

Commercially available refreshable Braille displays have changed little in the past 25 years. Today's displays do not differ substantially from what is described by Tretiakoff [1977]. Typical systems use cantilevered bimorph piezo-actuators (reeds) supporting vertical pins at their free end. Upon activation, a reed bends, lifting the pin upward. Braille characters are displayed by assembling six or eight of these mechanisms inside a package called a cell (see Figure 1(a))). A basic system includes 40 or 80 cells to display a line of text (Figure 1(b)), plus switches to navigate in a page (Figure 1(c)))[Stöger and Miesenberger1994].

While the elements of these cells are simple and inexpensive, the cost is driven by the necessity to replicate the cell 40 or 80 times, or more if one contemplates the display of a full page. Typical Braille displays cost much more than a personal computer.

1.2 Alternative Technologies

In recent years many alternate designs have been proposed, all sharing the principle of raising individual pins, or dome shapes, out of a surface [Blazie 1998, Roberts et al. 2000, Yobas et al. 2003]. In 2004 alone, no less than six U.S. patents related to Braille cells have been granted, and many others are pending [e.g., Peterson 2004, Yang 2004, Biegelson et al. 2004]. While most of the research focuses on reducing the cost of actuation, very little work is concerned with new approaches to the display of Braille.

Of note is a system proposed by Tang and Beebe [1998] who sandwiched discrete electrodes in a dielectric. The application of high voltage to these electrodes causes the skin to adhere locally to a glassy surface, thereby creating small tactile objects. Patterns resembling Braille characters could presumably be displayed with this method, however it appears to suffer from sensitivity to environmental factors such as humidity or skin condition.

Several investigators proposed the idea of a single display moving with the scanning finger rather than the finger scanning over an array of cells. Fricke [1997] mounted a single Braille cell on a rail and activated its pins with waveforms resembling "pink noise" in an attempt to imitate the effect of friction of the skin with a pin. Ramstein [1996] designed an experiment with a Braille cell used in conjunction with a planar "Pantograph" haptic device in an attempt to dissociate character localization from character recognition. The haptic device was programmed to indicate the location of the characters in a page, while the cell was used to read individual characters. Comparative tests were performed in different conditions with one or two hands. Again, the goal was to create an "array of Braille characters" with a single cell and reasonable reading performance could be achieved.

1.3 Overview

This paper reports on a feasibility study conducted to evaluate the potential of a new approach to the refreshable display of Braille. When the skin of the fingertip is locally deformed in the manner of a progressive wave, one typically experiences the illusion of objects sliding on the skin, even if the deformation contains no normal deflection [Hayward and Cruz-Hernandez 2000]. An electromechanical transducer was designed to create such skin deformation patterns with a view to investigate the feasibility of displaying Braille dots. The novelty of this approach lies in that it creates a progressive wave of lateral skin deformation, instead of a wave of normal indentation [e.g., Van Doren et al. 1987] or localized vibration [e.g., Bliss et al. 1970]. Our approach also relies on scanning motion, which is often mentioned as necessary to "refresh" the skin receptors and combat adaptation [Fricke 1997].

The transducer that we constructed was similar in principle to the 'STReSS' display [Pasquero and Hayward 2003], but had only one line of actuated contactors. This configuration allowed us to significantly increase the forces and displacements produced by the contactors. The Braille dots created by this device were "virtual" in that we attempted to recreate only the essential aspects of the skin deformation occurring when brushing against raised dots without actual physical dots.

The resulting system and the particular strain pattern - collectively termed "VBD" for Virtual Braille Display - were empirically designed with the assistance of the fourth author, a blind accessibility specialist, who also participated in the study in the capacity of "reference subject".

An experiment was conducted to tune the pattern's parameters to create a sensation as similar as possible to that experienced when brushing against physical Braille dots. The legibility of strings of truncated Braille characters - those comprising a single row of dots - was evaluated with five Braille readers on the VBD, and on a conventional Braille medium (embossed vinyl). The subjects' success rate and reading patterns were recorded and analyzed.

The study shows that reading with the VBD is possible with a high legibility rate given some personalization of the strain pattern. Reading is, however, more demanding and error-prone than on conventional media. More importantly, the study helped identify the strengths and weaknesses of the current prototype, and indicates how the device could be improved to yield a workable system.